With thousands of open-pit mines abandoned worldwide, increasingly stringent environmental rehabilitation legislation in Australia is paving the way for more effective long-term restoration efforts. Literally starting from the ground up, researchers at Flinders University are analysing mine waste, known as tailings, from various operations to develop innovative and sustainable systems capable of addressing one of the industry’s biggest challenges: mine drainage, which can cause significant environmental damage when not properly controlled.

The prediction and prevention of acid and metalliferous drainage (AMD) is one of the mining industry’s most persistent environmental problems, explains Professor Sarah Harmer, of the College of Science and Engineering at Flinders University.

“Combining geochemistry, mineralogy and microbiology, our teams are discovering how chemical and biological processes interact to accelerate — or, in some cases, slow down — the oxidation of sulfides in mine waste,” says Professor Harmer, author of a recent article published in the journal Environmental Geochemistry and Health, in collaboration with industry partners and scientists from the Flinders Accelerator for Microbiome Exploration.

“These studies are essential for mine closure and land restoration, providing crucial information about microbial interactions and their adaptation in operating mines and in abandoned areas,” adds the research team.

One of the factors frequently neglected in the origin of acid and metalliferous drainage is the presence of bacteria that thrive in the wastes. “These bacteria literally corrode the rock, releasing more acid and metals as byproducts of their activity, which can substantially exacerbate the problem over time,” explains the study’s lead author, Nick Falk.

“Just like a sick patient, we try to diagnose this kind of bacterial infection in mine waste. As it is difficult to observe these microorganisms, we resort to DNA-based analyses to identify which are present and what they are doing,” he underscored.

Analysis of multiple samples collected by industry partners is enabling researchers to paint a broader picture of the role of microbes in intensifying AMD and mine drainage, as well as proposing remediation solutions based on manipulating microbial processes.

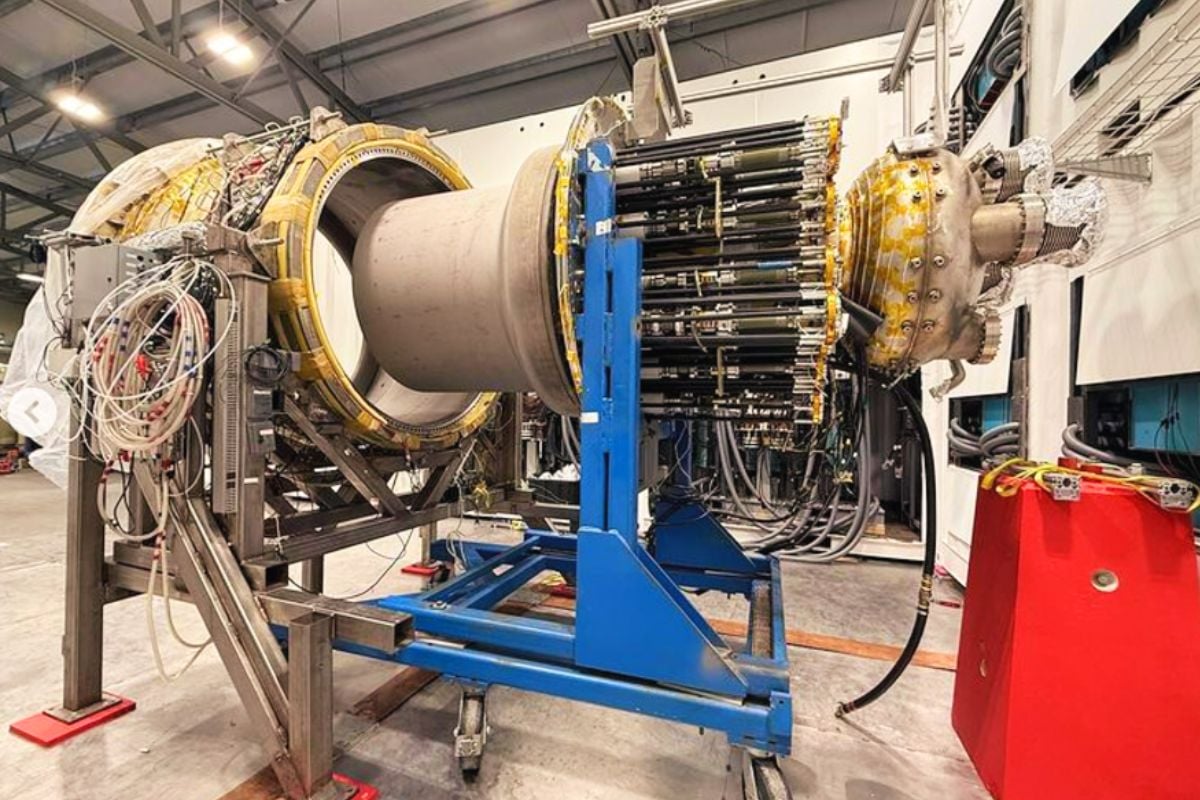

The five-year national project of the Cooperative Research Centre for Transformations in Mining Economics (TiME), known as “Project 3.10”, has already enabled leaching tests of up to two tonnes of waste from 12 mines, spanning from the Pilbara region in Australia to the Arctic Circle and the Gobi Desert in Mongolia.

“This work has given us unprecedented insight into the mechanisms of AMD formation under real conditions,” says Professor Sarah Harmer. “The initial results are changing the way researchers understand the relationship between microbial activity, mineralogy and acid generation over time, paving the way for smarter and more sustainable closure and rehabilitation strategies,” she adds.

The researchers now intend to test new remediation approaches before moving on to field-condition experiments.