A fleet of Canadian-built robots has illuminated the ocean’s hidden engine, revealing a massive store of living carbon long overlooked by surface-focused methods. By surveying phytoplankton from the surface to the deep, the team estimates a global biomass of about 314 teragrams—roughly 346 million tons—equal to 250 million elephants concealed beneath the sea’s shimmering skin. The finding reframes how scientists track carbon, climate feedbacks, and the pulse of marine life.

A silent census beneath the waves

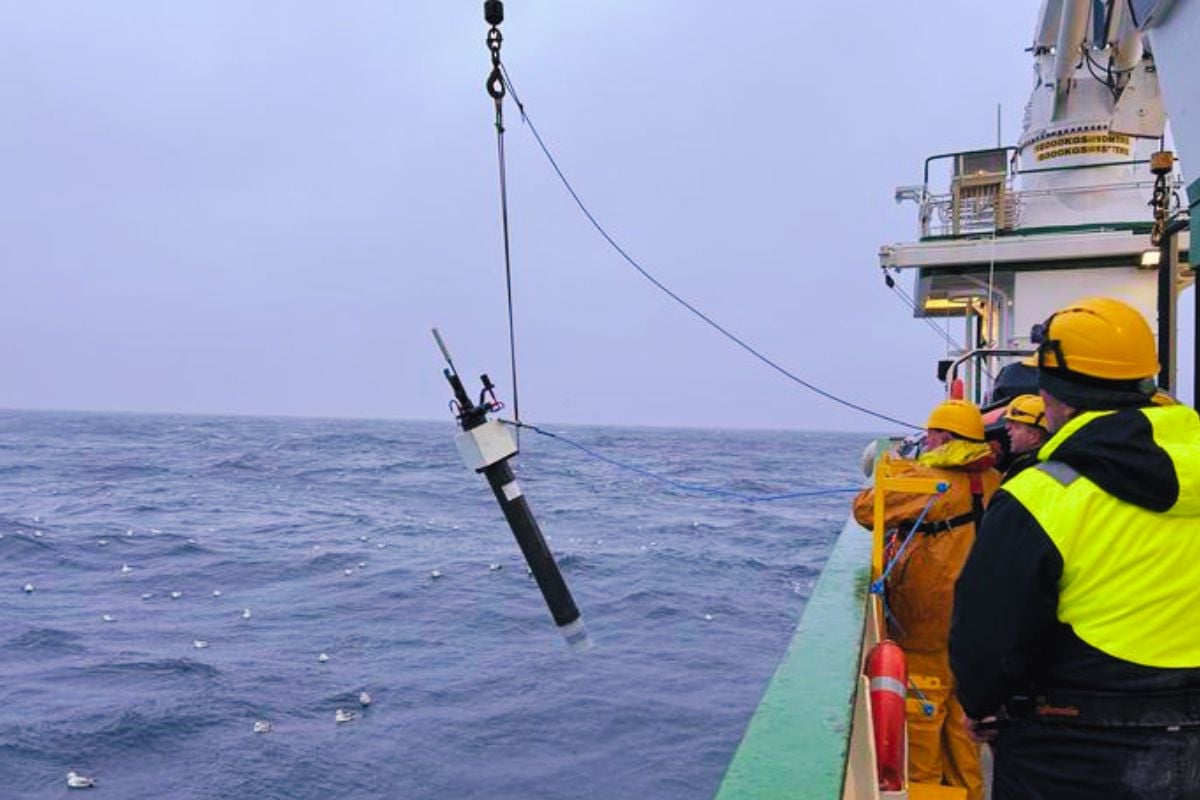

The Biogeochemical-Argo (BGC-Argo) network is a globe-spanning flotilla of autonomous floats that drift, descend, and ascend through the water column. Each profile records light, optical backscatter, and chlorophyll fluorescence, yielding a three-dimensional portrait of phytoplankton abundance. Over years of patrols, the fleet has compiled more than 100,000 vertical profiles, stitching together a dynamic view that satellites have long missed.

These robot platforms succeed where orbital sensors cannot, working under sea ice, cloud cover, and storm-tossed seas. By resolving biomass through the full depth, the floats capture the “missing” phytoplankton that lurk in dimly lit layers, especially at the deep chlorophyll maximum.

The magnitude of an invisible giant

Phytoplankton are microscopic plants, yet collectively they function as a planetary engine for carbon uptake and oxygen production. The new estimate—about 314 teragrams of biomass—translates to roughly 346 million tons, or the weight of 250 million elephants. That scale spotlights how much living carbon resides out of sight, below the ocean’s glittering surface.

These organisms produce around half the oxygen we breathe, while influencing climate through the drawdown of atmospheric CO2. Their shifting distribution shapes fisheries, coastal ecosystems, and the long-term chemistry of the ocean.

Why satellites fall short

Space-based sensors infer phytoplankton from surface color, tracing chlorophyll mainly in the sunlit skin of the sea. Yet many blooms peak at depth, where light is scarce but nutrients are available. Satellites also struggle beneath persistent clouds, within sea ice, and in optically complex coastal or riverine waters.

BGC-Argo closes these gaps by sampling day and night, in clear and turbid conditions alike. The result is a depth-resolved picture that complements space-based observations and improves global budgets of living carbon.

Key numbers at a glance

- About 314 teragrams of global phytoplankton biomass—roughly 346 million tons.

- Equivalent to the weight of 250 million elephants, distributed across Earth’s oceans.

- More than 100,000 vertical profiles recorded by the BGC-Argo fleet.

- Significant biomass exists beyond satellite reach, especially at depth and under ice.

A recalibrated perspective for climate science

Improved biomass estimates sharpen models of carbon uptake and atmospheric feedbacks. With tighter constraints, projections of ocean warming, oxygen loss, and productivity shifts become more reliable. That clarity matters for national policy, from fisheries planning to carbon accounting and ecosystem protection.

The depth-aware map also informs debates over ocean geoengineering, including proposals to fertilize waters with iron. Without precise baselines and regional context, interventions can trigger unintended consequences across food webs and biogeochemical cycles. “We’re uncovering a far larger, depth-resolved reservoir of living carbon than satellites alone reveal,” a lead scientist noted. “Any future intervention must be judged against this richer reality.”

How the robots change the game

Each float cycles between descent and ascent, measuring temperature, salinity, chlorophyll, and optical signals that correlate with phytoplankton carbon. Woven together across basins and seasons, these records expose phenology—when blooms start, peak, and fade—and how they respond to marine heatwaves, storms, and shifting currents.

Equally vital is continuity: standardized, long-term measurements that reveal subtle climate signals amid natural variability. Instead of fragmented snapshots, scientists gain coherent, basin-scale trends that resolve year-to-year change.

What comes next

The path forward includes expanding the fleet, refining sensor calibrations, and fusing float data with satellite imagery and ship-based surveys. Machine-learning tools will integrate these streams into near-real-time maps of global biomass, enabling earlier warnings for harmful algal blooms and ecosystem stress.

As floats venture deeper into polar and remote regions, the global picture will grow clearer and more actionable. The ultimate vision is a sustained, planetary observatory for ocean health—one that keeps pace with a rapidly changing climate and safeguards the ocean’s living foundation.

In revealing a biomass equal to hundreds of millions of elephants, the Canadian-led network has recast the ocean’s smallest drifters as a planetary-scale force. With eyes beneath the waves, science is closer to balancing the blue-carbon ledger, one profile at a time.