In the future, your clothing could come from tanks of living microorganisms. In an article published in the Cell Press journal Trends in Biotechnology, researchers demonstrate that bacteria can create fabrics and dye them in all the colors of the rainbow — all in a single “container.” This approach offers a sustainable alternative to the chemically intensive methods currently used in the textile industry.

“The industry relies on petroleum-based synthetic fibers and chemical dyes, including carcinogens, heavy metals and endocrine disruptors,” says the senior author and biochemical engineer San Yup Lee, from the Korea Advanced Institute of Science and Technology. “These processes generate large quantities of greenhouse gases, degrade water quality and contaminate soil, so we want to find a better solution,” he adds.

Known as bacterial cellulose, the fibrous network produced by microorganisms during fermentation emerges as a potential alternative to petroleum-based synthetic fibers, such as polyester and nylon.

To go further, Lee’s team sought to create fibers with vibrant natural pigments, cultivating cellulose-producing bacteria together with pigment-producing microorganisms. The microbial colors came from two molecular families: violaceins — ranging from green to purple — and carotenoids, which vary from red to yellow.

“In the beginning, we completely failed,” Lee recalls. “Either cellulose production was far below what we expected, or the color never set.” The team found that the cellulose-producing bacterium Komagataeibacter xylinus and the color-producing bacterium Escherichia coli interfered with each other’s growth.

By adjusting the “recipe,” the researchers managed to harmonize the microorganisms. For the cool-toned violaceins, they developed a delayed-co-culture approach, adding the color-producing bacterium only after the cellulose-producing bacterium had started to grow, allowing each to do its job without interfering with the other.

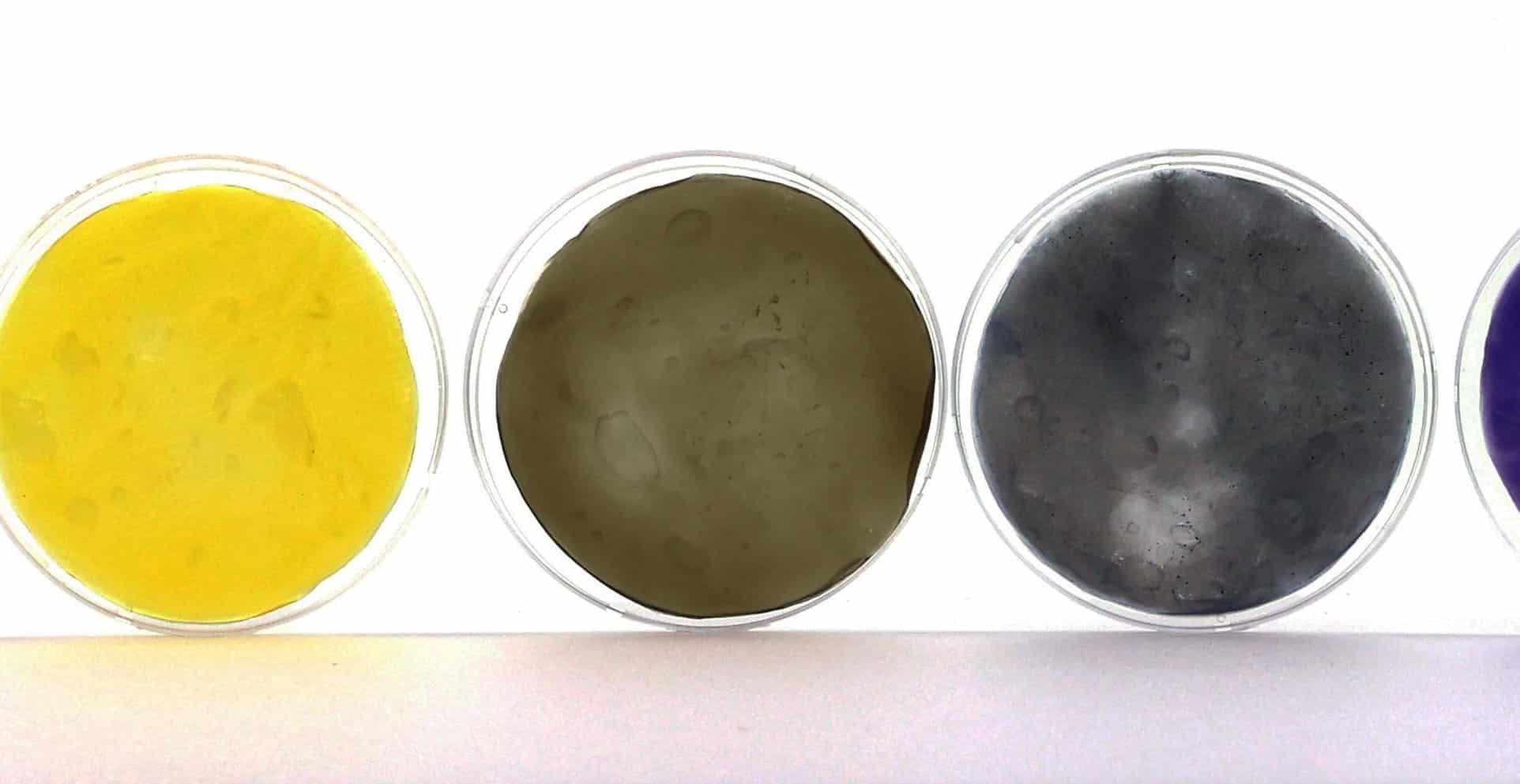

For the warm-toned carotenoids, they created a sequential culture method, in which the cellulose is harvested and purified first and then immersed in the pigment-producing cultures. Together, the two strategies yielded a vibrant palette of bacterially produced cellulose sheets in purple, navy blue, blue, green, yellow, orange, and red.

To test whether the colors endured daily use, the team washed, bleached, heated, and submerged the fabrics in acidic and alkaline solutions. Most retained the colors, and the violacein-based fabric even outperformed synthetic dyes in the washing tests.

“Our work will not immediately transform the entire textile industry,” acknowledge Lee. “But at least we have proposed an environmentally friendly direction for sustainable dyeing, producing cellulose at the same time.”

Lee estimates that bacteria-based fabrics are still at least five years away from stores. Scaling up production and competing with cheap petroleum-based products are among the remaining challenges. Real progress will also require a change in consumer mindset, valuing sustainability over price.

“It is our duty, as humans, to make the world a better place and allow our children to live happier lives,” Lee concludes. “This research is one of those efforts. Let us be kind to the environment and do something good for future generations.”